By Maranke Koster, Ph.D.

I am a basic scientist and a member of the Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) of the National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias (NFED). My research is focused on understanding the mechanisms that lead to the formation of skin and cornea erosions in ectodermal dysplasias. Specifically, we focus on ectodermal dysplasias caused by genetic changes in the TP63 gene. Two of these ectodermal dysplasias are ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip and/or palate (AEC) and ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting (EEC) syndrome, but there are others as well.

Although each TP63-related ectodermal dysplasia has different characteristics, and each affected patient is different, there are many similarities in clinical symptoms. Many patients with TP63-related ectodermal dysplasias experience skin or cornea erosions, thin/absent hair, limb abnormalities, and improper functioning glands in the eye. By investigating the molecular and cellular mechanisms that lead to these manifestations, we hope to contribute to the development of new treatments.

Using Patient Biopsies to Understand Skin Fragility

To study the basis of a human disorder, it is important to use human patient material. With help from the NFED and expert dermatologists, we have been fortunate to be able to collect skin biopsies from AEC and EEC patients during the past years. Some biopsies were used to produce microscopic sections of the skin. Other biopsies were used to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), lab-generated stem cells that can be used to generate any type of cell in the body, including skin cells. By creating iPSC-derived patient skin cells, we create new tools to understand the disease mechanism of ectodermal dysplasias.

Most recently, we have used the skin biopsies to understand why skin of AEC patients is often so fragile. To this end, we used the iPSC that we generated from AEC patient skin biopsies. We also generated a second set of iPSC in which we corrected the disease-causing TP63 variant. We then used these iPSC to generate keratinocytes, the cells that constitute the outer layer of the skin (epidermis) and that are responsible for the skin fragility in AEC patients.

Studying AEC Keratinocytes

We first wanted to determine if the AEC keratinocytes could properly adhere to proteins in the basement membrane, a structure that connects the epidermis to the rest of the body. This type of adhesion is important to provide structural integrity to the skin, to prevent blistering, and to allow for migration of keratinocytes during wound healing.

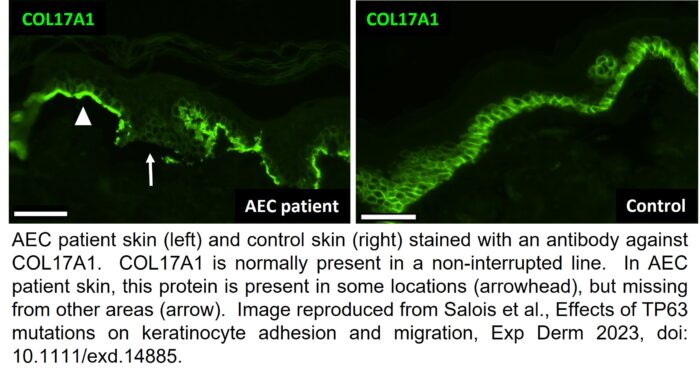

We found that AEC cells had a reduced ability to adhere to and to migrate on these basement membrane proteins. Consistent with these findings, we also found that AEC cells contained much fewer of the types of proteins that are important for allowing keratinocytes to adhere to the basement membrane. To ensure that these findings are applicable to AEC patients, and not just to cells in a dish, we also looked for the presence of these proteins in AEC patient skin. As you can see in the image above, a protein called COL17A1 is present in a non-interrupted line in normal skin. The green staining represents the area where the keratinocytes of the epidermis adhere to the basement membrane.

However, in AEC patient skin, COL17A1 is only present in a few locations (arrowhead) while it is missing from others (arrow). The locations where COL17A1 is missing are the locations where the keratinocytes cannot adhere properly to the basement membrane. In addition, in previous work, we found that AEC keratinocytes also cannot adhere to each other very well. We believe that the reduced ability of keratinocytes to properly adhere to each other and to the basement membrane may provide an explanation for the skin fragility in AEC patients.

Collaboration Is Critical to Success

There are many open questions that remain. For example, we do not know if the same defects in adhesion occur in EEC skin. Our preliminary experiments suggest that this might not be the case. Similarly, we do not know if the same defects occur in other TP63-related ectodermal dysplasias. In future work, we aim to address these issues and investigate the cellular and molecular basis for additional clinical abnormalities in TP63-related ectodermal dysplasias.

Finally, it is important to realize that this type of research can only be performed as a collaborative effort between the NFED, scientists, clinicians, and patients. None of this work could have been done without the continuous participation of patients. We are very grateful for the important insights we gained from interacting with patients and for the skin biopsies that patients have donated to this work. We could not do this without you!

- Maranke Koster, Ph.D. is a guest blogger for the NFED and a member of our Scientific Advisory Council. She is a Professor in the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology at Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina.

Hola! Soy de Mendoza Argentina! Tengo displasia ectodermica anhidrotica tp63 y estoy por hacerme trasplante de tejido de membrana amniotica ojo izquierdo. Pero le dijo un clínico que la enfermedad puede dejarme ciega. Estoy muy mal y necesitaría hablar con alguno de uds

I’m glad we were able to connect via email. We are still researching information to provide to you.