As we celebrate our 40th anniversary and reflect on the journey to this point, we can say with certainty that no other entity in the world has driven ectodermal dysplasias research more than the National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias (NFED). It’s been our honor to lead. Yet, the gratitude goes to the families who volunteered for studies, the curious researchers who strived to make a difference, and the donors who funded the vision.

Each research finding, big or small, has been a huge victory for the ectodermal dysplasias community. It gave us a piece of knowledge we didn’t have before. Our most extraordinary research success thus far is the development of a potential treatment for x-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED).

It began with the search for the responsible gene, and has led to today’s clinical trial of a protein treatment that has shown restoration of sweat gland function and increased development of other body parts when given to male fetuses with XLHED in utero. If successful, that treatment could be available on the market for all XLHED families by our 45th Anniversary! It’s an incredible story for a small nonprofit such as ours.

How It All Began

The ectodermal dysplasias were not on any investigators’ radar when the Foundation began in 1981. A review of the medical journals, where research findings would be published, would have yielded few articles. With a shortage of medical information, the NFED knew that only research would provide answers to families’ unending questions about their diagnosis. Research became central to our mission.

In 1982, the Foundation formed its first Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) to oversee its research efforts and determine what role we could play given our small size. Ronald J. Jorgenson DDS, Ph.D., FACMG, a dentist and geneticist who served as the SAC chair for the first 25 years, remembers those early days.

“Before NFED, little was known about the ectodermal dysplasias and nothing was known about their cause and effective treatment. Consequently, one of the first tasks for the SAC created at the onset was to set sights on a plan for description of the many types of ectodermal dysplasias, their demographics, the best treatment, and identification of causative gene defects. Ultimately, of course, the goal was to prevent their occurrence altogether. To this latter end, the Council directed research funds to various researchers and institutions to stimulate projects that would help so many wonderful people afflicted by the group of disorders affecting the ectoderm (outer covering of the body) and associated structures.

What an exciting and rewarding ride these researchers and institutions have taken us on! And, not only for those with ectodermal dysplasias; the discoveries made by our funded programs are being found useful for other genetic disorders as well.”

– Dr. Ronald J. Jorgenson

Granting Researchers Access to Patients

The Foundation was able to help researchers in a way that no one else could. As the only support organization for ectodermal dysplasias in the world at that time, the NFED could link researchers to affected individuals. The NFED’s founder, Mary Kaye Richter talks about how critical that was.

At the annual NFED Family Conferences, families voiced their questions and concerns. These informed research directions as SAC members listened and learned. Virginia P. Sybert, M.D. talked about one of the NFED’s earliest research successes. Dr. Sybert is a geneticist and pediatric dermatologist at the University of Washington who served on the SAC its first 25 years.

“The NFED has been a leader in the transition of support groups from unadorned support to movers and shakers in the efforts to push the frontiers of science and medicine forward. Without the efforts of the NFED, financial, political and participatory, the identification of the causal genes, the identification of potential treatment and the implementation of treatment would have happened much later, if at all, in terms of the potential treatments.

– Dr. Virginia P. Sybert

“I will never forget when Nan Esterly and I sat in front of the families on the podium, secure in our ‘expert’ knowledge, and several parents in the audience asked about the association of ichthyosis and ectodermal dysplasia,” Dr. Sybert said. “We looked at each other and sagely said, ‘oh no, no relationship.’ But enough parents chimed in about their peeling babies and their “post-mature” babies that we realized we might be just a little stupid.

So we created-the SAC and the NFED staff-a survey, the results of which showed that collodion membrane, previously believed to be a sign of many ichthyoses, was also a feature of ectodermal dysplasia and the results were published in the Journal of Pediatrics with the first ever(!) authorship by a group, not by a person:

Scaling skin in the neonate: a clue to the early diagnosis of X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome). The Executive and Scientific Advisory Boards of the National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias, Mascoutah, Illinois. [No authors listed] J Pediatr. 1989 Apr; 114(4 Pt 1):600-2. PMID:2926570

We fought the journal to get them to do this because we believed so strongly that it was the result of a total group effort. We made the same sort of study about the gastrointestinal complaints. Without research, we’re just spinning our wheels.”

Families Get the Credit

We agree with Dr. Sybert. You cannot talk about ectodermal dysplasias research success without first mentioning our families. Since the very beginning, affected families have been eager to help researchers by sharing their personal information.

Throughout the years, they have filled out numerous surveys that have asked them about everything from peeling skin, constipation, and breastfeeding to their quality of life, hearing, and dental implants. Many have provided blood, skin, and hair samples while others have been weighed and measured, all in a singular quest to learn more. They should feel incredibly proud for their role in expanding the knowledge found in the medical and dental literature.

Funding Research

Providing patient access was key, but we knew the Foundation needed to offer financial grants as well. In the late 1980s, Pegie Gault, an NFED mom from Michigan, was greatly concerned about the lack of research and began her own personal fundraising campaign to make a difference. Knowing that the research fund must grow a great deal in order to find the answers to some of the more complex questions, the NFED embarked on a special campaign in 1991 to raise additional funds for research. This was also a way to celebrate our 10th anniversary. Dr. Arthur Nowak challenged us to find 1,000 donors willing to give $100 to raise the fund to $100,000. As a result, the 999 Club was born.

According to NFED’s executive director, Mary Fete, the Foundation’s financial grants have always served as seed grants to researchers.

The NFED’s role is not to fund millions but to foster research through seed money for grassroots efforts. Investigators cannot get large scale funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) without already having some preliminary results. Our grants enable them to conduct initial studies to get that data. And, we have done that very successfully. I am incredibly proud that, since 1989, we have funded more than $3.6 million to researchers.

– Mary Fete

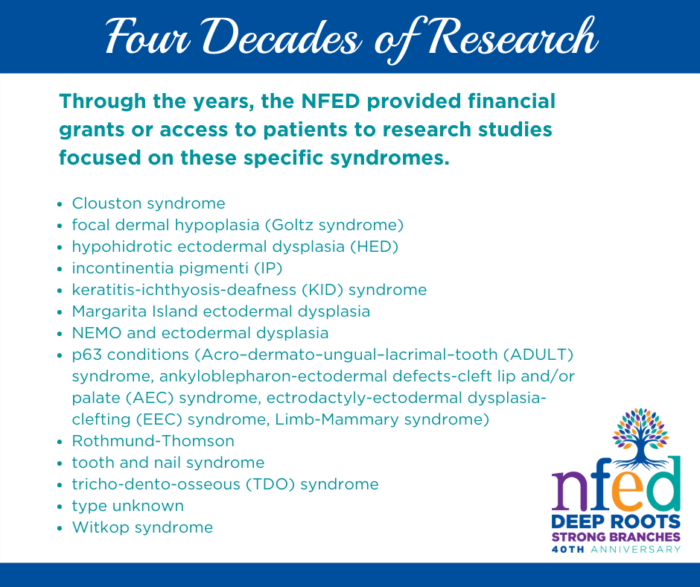

Syndrome Specific Research

The dream is to better describe a specific type of ectodermal dysplasia and develop treatments for it. Without a doubt, NFED’s research efforts over the past four decades have made the most impact on the most common type of the 100+ ectodermal dysplasias, hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED).

In 1989, Dr. Jonathan Zonana, emeritus Professor in the Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics at Oregon Health Sciences University, was the first researcher to receive access to patients and a $10,000 financial grant from the NFED for his work to identify the gene for HED.

“The NFED played a crucial role in the discovery of the genes associated with HED,” Dr. Zonana said. “Their first research grant was startup funding to search for the genetic causes of HED. This seed money led to subsequent successful National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for these ‘orphan disorders’. In addition to the funding, NFED members participated in the clinical research studies donating both time and blood to the effort. The NFED support led to eventual molecular diagnosis, understanding of pathogenesis and now treatment.

Mary Kaye talks about the extraordinary journey of finding the gene for XLHED to developing an in-utero treatment that restores sweat gland function and improves other symptoms that is in clinical trials today.

The 1990s

By the second half of the nineties, our research efforts began to pick up speed. Genes for XLHED and Clouston syndrome were found, and the NIH sponsored a major scientific meeting on the ectodermal dysplasias, which highlighted research achievements, needs, and direction for the future. An anonymous gift of $100,000 enabled the Foundation to expand its research portfolio. It became clear that the Foundation needed a dedicated staff person to oversee the growing research activities, which led to Mary Fete joining the staff!

The 2000s

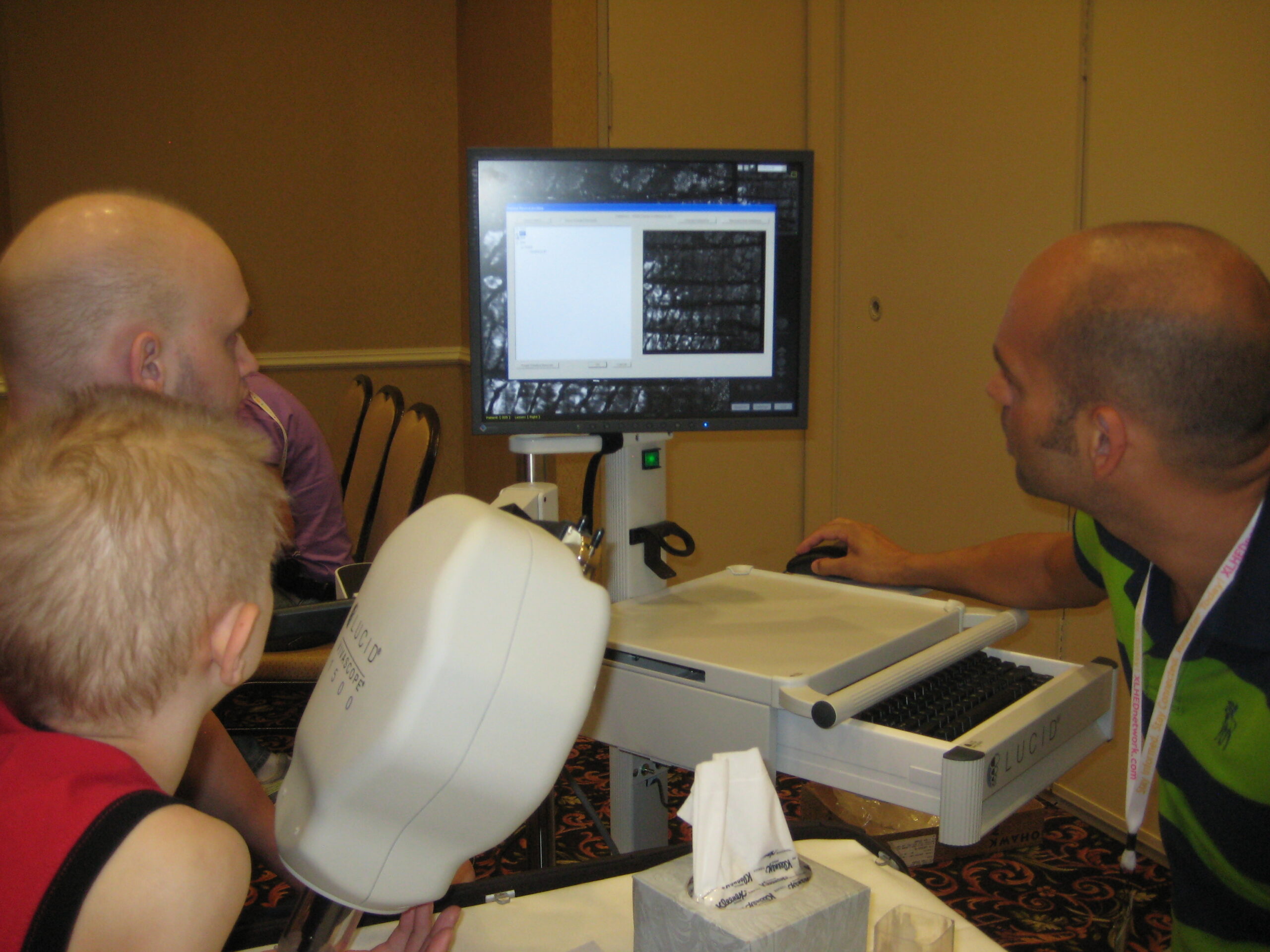

The Geismar family began the Halloween Bash in Manhattan in 2001. The fundraiser generated larger sources of income to fund research, which enabled the Foundation to increase its financial grants. Getting researchers interested in rare disorders isn’t easy. With a growing list of research needs, the NFED decided to conduct its own studies. Members of the SAC embarked on several clinical research projects in this decade. Research became a bigger portion of the annual Family Conferences, as the event provided investigators with access to a larger patient sample all located in one place. And, the families were eager to participate.

These clinical projects provided valuable results. Some of the key NFED-sponsored studies from this time documented the following:

- The very first study on how ectodermal dysplasias specifically affect women showed their issues with sweating, puberty, breast development, breastfeeding, and infertility.

- The allergy and asthma study demonstrated that children affected by ectodermal dysplasias were prone to more allergies and asthma than the general population.

- The cognitive study dispelled the myth that HED affected an individuals’ cognitive ability. It found that youth were similar to their unaffected peers on standardized measures of cognition, academic achievement, and adaptive functioning. Although, children with HED may be at increased risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Another study documented that children affected by ectodermal dysplasias experienced growth abnormalities at an early age and through adolescence.

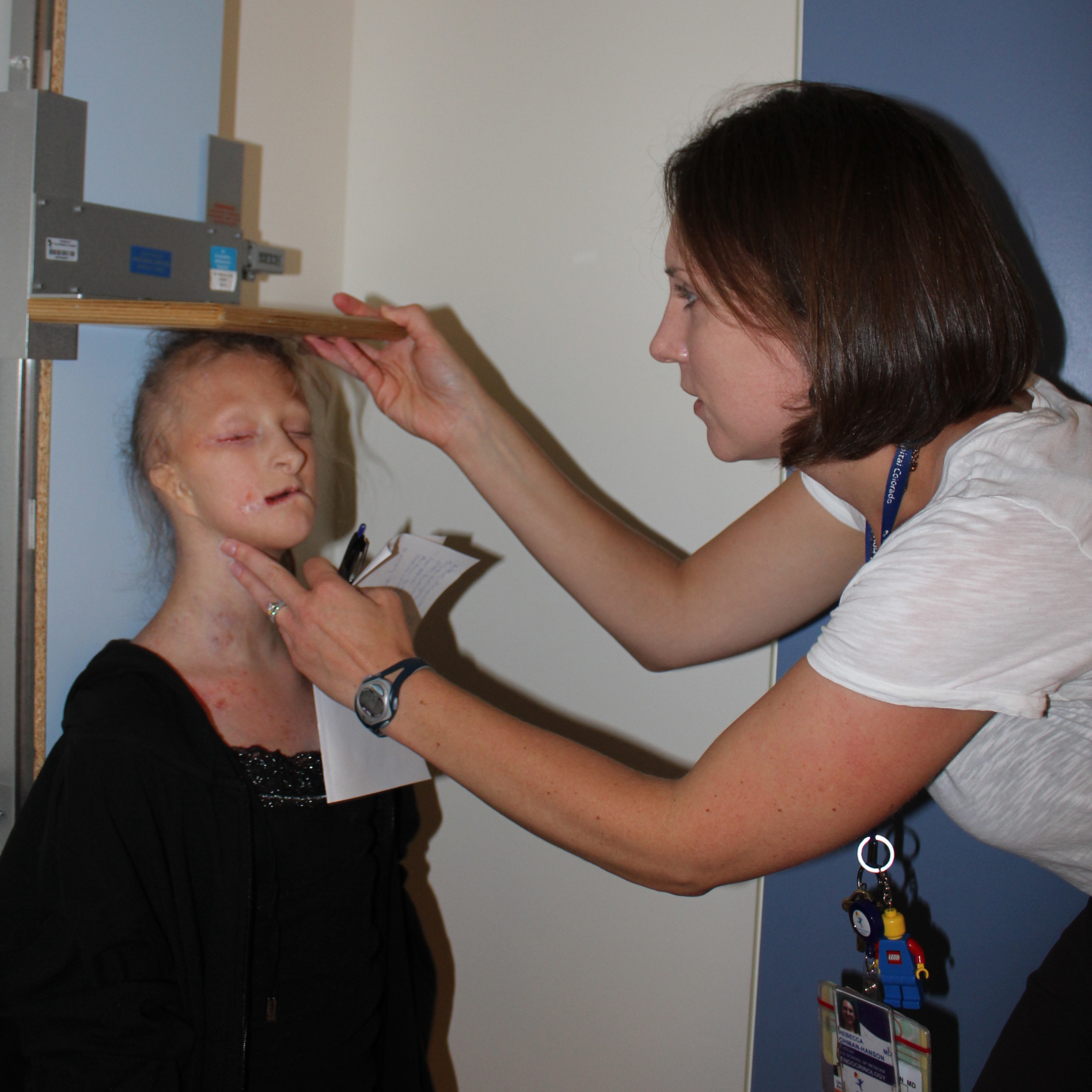

Scientific Conferences

Through the years, the NFED has successfully sponsored 10 scientific conferences to kick-start new research initiatives by bringing experts from around the world together. Landmarks workshops in 2003 and 2006 focused on learning more about ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/and or plate (AEC) syndrome and the devastating, often life threatening, skin erosions associated with it. Numerous publications emerged that better described the condition and created the first protocol for treating the painful skin erosions so that children survived. Today, NFED-funded researchers continue to explore ways to use a person’s own stem cells to treat these erosions.

What’s an Ectodermal Dysplasia?

What is and isn’t an ectodermal dysplasias has been an ongoing conversation for 40+ years. For a long time, the NFED used Dr. Newton Freire-Maia’s framework as a guide to answer that question. With the wealth of new knowledge from genetics, the Foundation held the Classification Conference in 2008 to explore how a new approach could improve ways for families to get diagnosed. This launched a decade-long effort in which our experts developed a new working definition of what is an ectodermal dysplasia as well as a new classification system.

The Fourth Decade

With so many types of ectodermal dysplasias, another ongoing debate is this: Do we focus on a lot of projects in a small way or a few projects in a major way. Of course, if we had the resources, we would love to do it all! The Foundation spent the 2010s laser focused on several key areas:

- Launching the first Ectodermal Dysplasias International Registry to capture critical data and link patients to researchers conducting clinical trials.

- Collaborating with Edimer Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Holm Schneider, EspeRare and Pierre Fabre on the ongoing development of a treatment for XLHED.

- Sponsoring two research conferences to better understand focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome) which yielded several medical publications.

- Supporting efforts to find treatment solutions for the skin erosion and eye issues experienced by people affected by syndromes caused by the p63 gene.

The Fifth Decade

Our 40th anniversary seemed like the perfect time to once again gather the world’s best minds and envision what our Research Program should target for the next decade. Last fall, physicians, scientists, and researchers convened at our International Ectodermal Dysplasias Research Conference: Translating Discovery to Therapy.

They identified the following five areas of research with different work groups leading each: incidence and prevalence of ectodermal dysplasias; wound healing; better pathways, registries, and biobanks; and diagnostics. These work groups have begun to meet and chart a way forward.

Our Relentless Pursuit

We are incredibly proud that families facing a new ectodermal dysplasia diagnosis in 2022 have an incredible amount of information to access compared to those in 1981. It’s taken an extraordinary amount of work, financial resources, and persistence, but it’s all been worth it. Research is always a long-term investment in a dream of what might be.

Mary Fete said, “Despite our successes, which is impossible to list all of them here, so many more questions remain. Our vision and mission are as clear now as it was a few decades ago: leading the charge to improve diagnosis and find the best treatments for you, our families. Can you even imagine what discoveries we will make in the next 40 years? It’s exciting to think about and work for. And, we look forward to doing it—together!”

Dr. Jorgenson gives us the final word.

Speaking for myself (and, I’m sure for other SAC members), I can say unequivocally that my association with the Foundation, the research projects, and the families involved has been a highlight of my personal and professional life. May the bounty continue to flow and may the smiles continue to light the world.

– Dr. Jorgenson